Tetiana escaped from the war in Ukraine and has stayed as an artist in residence at t e k s a s AIR from 12th March – 12th August 2022. Her stay has been supported by Displaced Artists Network, as well as the translation of her essay below, written during her stay.

Tetiana Burlachenko was born in Pavlograd, a city in eastern Ukraine. She obtained a Bachelor degree in Philosophy at Oles Honchar DNU (Dnipro, Ukraine) and a Master degree in German Philosophy at SPSU (Saint Petersburg, Russia). Besides that, she has studied Curatorial Studies at the online-school “The Conception”. As a writer of academic and media publications Tetiana works in the field of philosophy and contemporary art. Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine she participates in activist initiatives supporting civilians and the army of Ukraine.

Wandering Through the War: Between the Text and the Graveyard

by Tetiana Burlachenko, 2022

Life during a full-scale war in Ukraine is full of desperate attempts to comprehend the immeasurable number of human losses. A lot of the people die because of body mutilations, many simply disappear after successive rocket strikes. Constant flipping through the news, photos viewing, listening and reading of the words of witnesses, allows one to more clearly understand the scale of destruction that continues to be inflicted on civilians by Russian weapons.

For many refugees, images and videos of destroyed buildings hiding people under them are intertwined with the undisturbed landscapes of European cities. The need to understand and record the gap between the circumstances in Ukraine and Denmark has worried me. Aimless wandering through the streets of Danish towns became, in a way, a journey towards understanding how to perceive the world around us henceforth. Any attempt to deal simultaneously with the reality on the smartphone screen and the life on this side of it, seemed shaky. Gradually, this doubt-filled tour turned into a search for a new way of viewing and interpreting the war.

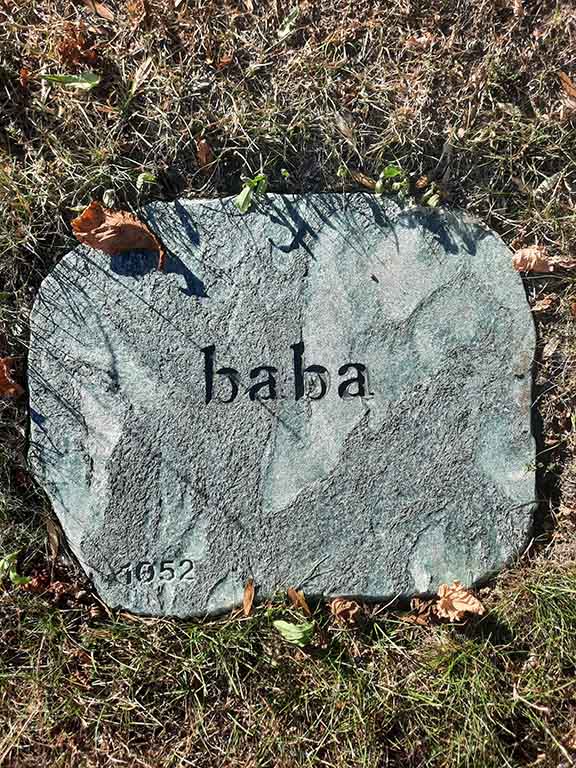

Wandering along cemeteries was the first impetus for this. The process of reading the inscriptions on the tombstones of the two Copenhagen cemeteries – Assistens Kierkegård and Vestre Kierkegård turned out to be similar to scrolling through a news feed – often the information about lost and dead is narrowed down to indication of their names. The “reading” of the cemeteries seems to unite the time dimension of the past with the present, which was broken with the beginning of a full-scale war. Buried in their own graves, under rubble and in pits of mass graves – how are the deaths of the dead of peace and the dead of war combined?

I remembered the initiative of Gregor (Hryhorii) Malantschuk, a Ukrainian-Danish philosopher and researcher of Soren Kierkegaard’s creative heritage, who introduced Kierkegaard Study Circles in Copenhagen in the second half of the fifties. The format of the circles was foreseen for the association of people with different backgrounds and different views. At Malanchuk’s initiative, they gathered together to jointly discover new possible interpretations of Kierkegaard’s works. Taking this path today, would it not be possible to consider cemeteries as the main subject of consideration of participants of the circles he introduced? Are the inscriptions on the cemeteries first of all a text, that announces death? Death, the meaning of which was ultimately sought by Kierkegaard himself (as, for example, in the section “The Decisiveness of Death, At the Side of a Grave” in his book “Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions”). It does not seem accidental that the meaning of Kierkegaard’s surname – cemetery – indicates a place where the feeling of grief receives its fulfillment.

Thinking about the affinity of the architecture of cemeteries with the structure of the text directed my movement further. First I started my walk from Assistens Kirkegård and after looking at Kierkegaard and his family members’ tombstone I went to Vestre Kierkegård, where I wandered around looking for Malantschuk’s burial place. This walking ritual reminded me of Kierkegaard’s long and exhausting wanderings in and around Copenhagen (including the places where I live now). In a sense, I see a number of my wanderings as a re-enactment of his walks. On YouTube, I came across the short film “Kierkegaard” by the Croatian director Igor Bezinovic, who visited Soren Kierkegaard’s grave 7 years before me. In his video, he explains that in his first year of study at the Faculty of Philosophy, he planned to make this trip by the first opportunity to visit Copenhagen. Such a pilgrimage to the philosophical shrine, inspired by an interest in the legacy of Kierkegaard, seemed to me a sign of the kinship between wandering and reading. According to Guy Debord, drifting along city streets aims to reassign alienated urban space to wanderers. What exactly is then drifting along the graves? Probably, we are talking now about the return of the ability to read after the initial shock of the war, which due to the incessant flow of news contributed to the narrowing of all the possible semiotic load of the text to the text-as-a-sign-of-loss. The awareness of the text, as such, became connected at a deep level with the ability to constantly keep, within the limits of attention, information about an infinite number of deaths. Considering this, wartime reading practices together with repeated glances at the news feed, are embodied through cemetery wanderings.

But due to the absence of any signs of the deceased, not all deaths are subject to “reading”. Such, on the other hand, remain anonymous and need the comments of living witnesses in order to be identified. The diversity of deaths, evidenced by tombstone inscriptions in cemeteries, and a number of burials as a result of shelling of Ukrainian cities, is striking. As the result of explode, the bombs tear apart the bodies of people and animals, and the fires caused by the explosions, burn them to such an extent, that they are, sometimes, beyond identification. Nameless mass burials in the territories, that were or continue to be under occupation (some of them, including Mariupol, for the second time since 2014), burials with numbers instead of names, burials in homesteads or children’s playgrounds require a new awareness of documentation and text meaning, that inform about these incomprehensible forms of death.

In the Immigrantmuseet in Farum I came to see the temporary exhibition about the life of refugees, who came from Ukraine to Denmark. After watching it, it was unexpected to come across the exhibition “Dead and Buried”, dedicated to the graves of migrants and refugees in Copenhagen cemeteries. Paradoxically, the museum highlights the stories of refugees arriving from territories full of dead bodies, including the unburied or anonymously buried, and at the same time the photograph of the mass burial pit and tombstones in the museum space represents the scenarios of migrant and refugee fates. Malantschuk, in fact, was one of these migrants, who moved from Ukraine as a young man, first to Germany, and then to Denmark after his home in western Ukraine was destroyed during the First World War and his parents died after it ended. The meaning of Kierkegaard’s heritage study groups conducted by Malanchuk deepens with an attempt to read his own burial place as part of the same heritage – the collective text of the dead. Reading it involves wandering between bodies. A walk among the tombstones becomes a reading lesson the sense of which coincides with Kierkegaard’s “silent lesson of dying” – mastering the cemetery by work of recognizing the multitude of signs that testify death. On the other hand, the practice of reading is likened to wandering between buried and unburied, missing bodies and found names. The text becomes a type of cemetery, imprinting the destinies affected by the war. This essay embodies and continues my own way of moving against the background of war – a slow search for a path that runs simultaneously through the text and the graveyard.

References:

Debord Guy, “Theory of the Derive”, translated by K. Knabb, situationist international online [https://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/theory.html].

Hong V. Howard, Hong H. Enda, “Gregor Malantschuk”, Søiren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers, 1982, Vol. 13; Iss. 4, p. 228-232.

Kierkegaard Søren, “The Gospel of Sufferings”, translated by A.S. Aldworth and W.S. Ferrie, James Clarke & Co (March 26, 2015), 150 p.

Kierkegaard Søren, “Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions”, translated by H. V. Hong and E. H. Hong, Princeton University Press, 1993, 204p.

Translated by Tetiana Petrovska

Photo series: Tetiana Burlachenko, from Assistens Kirkegård and Vestre Kirkegård